I thought this description of a young child waking up, in the novel Independent People by Halldor Laxness, was great:

Were they afraid to wake up, or what? He began tapping quietly with his fingernails on the sloping roof, a thing he could never, in spite of threats, restrain himself from doing when he felt that the morning was being prolonged too far. When this had no effect he began to squeak, first like a little mouse, then sharper and higher, like the squeal of the dog when you tread on its tail, and finally higher still, like a land wind shrieking through the open door.

"Now then, that's enough of your nonsense."

It was his grandmother. The boy had succeeded, then. (pg. 147-148)

Wednesday, August 19, 2009

Friday, August 14, 2009

I'm amazed by how many survived

Reading about the difficult living conditions (damp sod huts together with wind, snow and rain, a limited diet, disease, volcanic eruptions) in past centuries in Iceland, I’m not surprised to learn that the death rate was high. According the interesting book, A Ring of Seasons, 30% of children born in Iceland from 1750 to 1850 died within their first year. Between 1757 and 1845, 43% died before the age of 14. There was no doctor in the country until 1760.

One possible reason the author gives for the high death rate (among many others) is that the women rarely breastfed. This might have been due to the fact that the mothers worked hard and their milk therefore dried up quickly. Some babies died of malnutrition on watered-down cow’s milk.

Other sanitary conditions were also frightening. Women washed their hair in urine on the weekends, but otherwise, people almost never bathed. Sheets were washed once or twice a month, underwear less often. Trash was thrown into the central pond in Reykjavik and in other towns, collected behind the houses until dumped on the shore for the sea to take away. Lucky for Iceland, they didn’t have rats for a long time.

Children worked hard with little rest and Icelanders started to grow taller only after they were able to lessen their workload a bit.

Given these conditions, what surprises me is not the high death rate, but the fact that people survived and carried on to procreate. Living standards in Iceland have been good since World War II and now probably surpass the U.S. (yes, it can be cold and dark, but it seems the Icelanders have been genetically selected to tolerate the dark better than others). Still, when I look at people and think of what their descendants went through, from the Viking settlers to the women kidnapped from Ireland and brought over here, to the natural disasters and the poor conditions, I’m amazed by those who survived.

One possible reason the author gives for the high death rate (among many others) is that the women rarely breastfed. This might have been due to the fact that the mothers worked hard and their milk therefore dried up quickly. Some babies died of malnutrition on watered-down cow’s milk.

Other sanitary conditions were also frightening. Women washed their hair in urine on the weekends, but otherwise, people almost never bathed. Sheets were washed once or twice a month, underwear less often. Trash was thrown into the central pond in Reykjavik and in other towns, collected behind the houses until dumped on the shore for the sea to take away. Lucky for Iceland, they didn’t have rats for a long time.

Children worked hard with little rest and Icelanders started to grow taller only after they were able to lessen their workload a bit.

Given these conditions, what surprises me is not the high death rate, but the fact that people survived and carried on to procreate. Living standards in Iceland have been good since World War II and now probably surpass the U.S. (yes, it can be cold and dark, but it seems the Icelanders have been genetically selected to tolerate the dark better than others). Still, when I look at people and think of what their descendants went through, from the Viking settlers to the women kidnapped from Ireland and brought over here, to the natural disasters and the poor conditions, I’m amazed by those who survived.

Labels:

breastfeeding,

children,

hygiene,

Iceland,

work

Thursday, August 13, 2009

The parents are tired

I spoke to my parents last night and for the first time, since I left River with them two weeks earlier, they sounded tired. They maintained a stoic front. My dad said they were holding up, but admitted that his nap from 11-2 kept them homebound. My mom told me all the new words he’s picked up, how bright and quick she thinks he is, and how easy-going he is. Yet she said if she has to go after another car, ball or Elmo she’s going to pass it on to my dad. And she did break a bone in her foot since I left.

Now that Mark is gone, I feel bad hanging out in Iceland alone while my parents watch my child. Originally, I had planned to take a hike or do something adventurous, which Mark wasn’t so interested in. But I wasn’t able to set something up for this particular day. So instead, I spent the day walking around town, visiting museums, eating a fantastic meal and reading.

I suppose I need to appreciate the time while I have it. In just over 24 hours, I’ll be back to full-time parenthood, my day defined by naps, meals and pottying. I’m excited to see my baby and to have my buddy around again. But for now, I’ll enjoy the quiet and the lack of interruptions.

Now that Mark is gone, I feel bad hanging out in Iceland alone while my parents watch my child. Originally, I had planned to take a hike or do something adventurous, which Mark wasn’t so interested in. But I wasn’t able to set something up for this particular day. So instead, I spent the day walking around town, visiting museums, eating a fantastic meal and reading.

I suppose I need to appreciate the time while I have it. In just over 24 hours, I’ll be back to full-time parenthood, my day defined by naps, meals and pottying. I’m excited to see my baby and to have my buddy around again. But for now, I’ll enjoy the quiet and the lack of interruptions.

Wednesday, August 12, 2009

Dinner with an Icelandic Family

I was recently invited to dinner by a kind Icelandic family with three children, ages 13, 10 and 4. Over grilled fish, roasted sweet potatoes, and ratatouille, I was able to learn more about family life in this northern country.

I asked the mother, Gurri, about the numerous baby carriages. Were Icelanders having a lot of babies or were they just taking them outside more often? She thinks they are having more babies. “It’s become a bit of a trend, during the recession,” she said. “You see carriages and pregnant women everywhere you go.”

Icelandic law allows for three months maternity leave, three month paternity leave and another three months to be used by either parent. Children can get a spot in a daycare somewhere between ages one and two. Until then, they rely on parents, grandparents, relatives or “home-mommys,” which are in-home daycares where up to five young children can be cared for.

Gurri pays just over $200 per month for full-time daycare for her son, including a full menu of home-cooked meals. This is thanks to government subsidies. She had been working full-time when she became pregnant with her third. Finding it too difficult to balance three children with a full-time job, she quit and stayed home for a year and a half. Now she is back at work. She gets up at 6:30 to go to the gym before work, then works an eight hour day. Her son’s daycare is less than a block away from home and her daughters’ school is just around the corner, within walking distance. The entire family sits down for dinner together in the evening.

In the summertime, her two elder daughters are largely on their own. The eldest, who is very involved in gymnastics, spends much of her days training. The 10-year old hangs out at home alone, plays with friends and visits her grandparents, who live within walking distance.

Icelanders get at least 24 days of vacation per day. In addition, they get 2 sick days per month for themselves and two days per month to care for their children. “So when we call in sick, we have to specify whether we are sick or our children are sick,” Gurri said.

They spent several years living in the U.S. The short vacations and poor social support offered in the U.S. led them to return to Iceland. “It was a serious factor we considered when we were deciding whether or not to stay there,” she said. “We would go to Iceland to see family in the summer for 4-6 weeks at a time. That just wasn’t possible with the vacation available at a U.S. job. Also, the daycare is so expensive and it’s very hard with no family nearby. In the U.S., your friends become your family.”

All of the children seemed to be affected by the daylight which lasts until well past 11 p.m. The 10-year old had slept until noon and was wide awake. The 13-year old had been up until 4:30 in the morning and was exhausted. The four year old was up several hours past his bedtime. His mouth smeared with chocolate from dessert, he put on a Viking cap with horns and accompanied me to the bus stop at 10:30 p.m., looking out for monsters to fight along the way.

The family lives in a duplex in a suburban neighborhood. Their home is spacious and airy, but they have only three bedrooms and the four-year-old still shares a room with his parents. “I’d really like to stay in this neighborhood and find a house with one more bedroom,” said Gurri. “But they don’t come up very often and they are very expensive.” Another option might be to turn half of the heated garage into another room.

Even though everyone had been occupied during the day, the family managed to put together a nice meal and enjoy an evening together. The 13-year old made the dessert – skyr and marscapone cheese with maple syrup and berries. The father grilled the massive piece of halibut, which fed five with much to spare. And mom took care of the side dishes. They were relaxed and friendly with each other. They had recently returned from visiting family in Scandinavia. While they were gone, the 4-year-old had his birthday. But it’s important that grandparents and relatives are invited to the party, so they all assembled when they returned.

The quality of life appealed to me – the reasonably priced quality daycare, having everything so close to home, the close family relations, the reasonable work schedule with adequate leave and the ability to spend long, relaxing evenings together. It’s the type of balance I strive for.

I asked the mother, Gurri, about the numerous baby carriages. Were Icelanders having a lot of babies or were they just taking them outside more often? She thinks they are having more babies. “It’s become a bit of a trend, during the recession,” she said. “You see carriages and pregnant women everywhere you go.”

Icelandic law allows for three months maternity leave, three month paternity leave and another three months to be used by either parent. Children can get a spot in a daycare somewhere between ages one and two. Until then, they rely on parents, grandparents, relatives or “home-mommys,” which are in-home daycares where up to five young children can be cared for.

Gurri pays just over $200 per month for full-time daycare for her son, including a full menu of home-cooked meals. This is thanks to government subsidies. She had been working full-time when she became pregnant with her third. Finding it too difficult to balance three children with a full-time job, she quit and stayed home for a year and a half. Now she is back at work. She gets up at 6:30 to go to the gym before work, then works an eight hour day. Her son’s daycare is less than a block away from home and her daughters’ school is just around the corner, within walking distance. The entire family sits down for dinner together in the evening.

In the summertime, her two elder daughters are largely on their own. The eldest, who is very involved in gymnastics, spends much of her days training. The 10-year old hangs out at home alone, plays with friends and visits her grandparents, who live within walking distance.

Icelanders get at least 24 days of vacation per day. In addition, they get 2 sick days per month for themselves and two days per month to care for their children. “So when we call in sick, we have to specify whether we are sick or our children are sick,” Gurri said.

They spent several years living in the U.S. The short vacations and poor social support offered in the U.S. led them to return to Iceland. “It was a serious factor we considered when we were deciding whether or not to stay there,” she said. “We would go to Iceland to see family in the summer for 4-6 weeks at a time. That just wasn’t possible with the vacation available at a U.S. job. Also, the daycare is so expensive and it’s very hard with no family nearby. In the U.S., your friends become your family.”

All of the children seemed to be affected by the daylight which lasts until well past 11 p.m. The 10-year old had slept until noon and was wide awake. The 13-year old had been up until 4:30 in the morning and was exhausted. The four year old was up several hours past his bedtime. His mouth smeared with chocolate from dessert, he put on a Viking cap with horns and accompanied me to the bus stop at 10:30 p.m., looking out for monsters to fight along the way.

The family lives in a duplex in a suburban neighborhood. Their home is spacious and airy, but they have only three bedrooms and the four-year-old still shares a room with his parents. “I’d really like to stay in this neighborhood and find a house with one more bedroom,” said Gurri. “But they don’t come up very often and they are very expensive.” Another option might be to turn half of the heated garage into another room.

Even though everyone had been occupied during the day, the family managed to put together a nice meal and enjoy an evening together. The 13-year old made the dessert – skyr and marscapone cheese with maple syrup and berries. The father grilled the massive piece of halibut, which fed five with much to spare. And mom took care of the side dishes. They were relaxed and friendly with each other. They had recently returned from visiting family in Scandinavia. While they were gone, the 4-year-old had his birthday. But it’s important that grandparents and relatives are invited to the party, so they all assembled when they returned.

The quality of life appealed to me – the reasonably priced quality daycare, having everything so close to home, the close family relations, the reasonable work schedule with adequate leave and the ability to spend long, relaxing evenings together. It’s the type of balance I strive for.

Saturday, August 8, 2009

Surrounded by Babies

This afternoon, Mark and I sat outside a Reykjavik café, drinking hot chocolate and eating waffles with jam and cream. A gay pride festival is taking place and the streets were crowded with Icelandic families coming to see the parade and the concert. Parents pushed babies in prams that are like portable wombs. They carried them on their shoulders. Some toddlers rode bicycles, or sat in bike trailers. They carried rainbow flags and sucked on rainbow lollipops. Their older siblings wore rainbow colored luaus. I hardly saw any signs of homosexual couples or families. I saw only a unified acceptance and a normalcy involved in taking the children to the gay pride festivities, even with a pole dancer in the parade.

This made me want to live in a more European progressive country. It made me want to bring River to such a parade and for him to take in events promoting the homosexual lifestyle as nothing out of the ordinary. I want him, like the Icelanders there, to accept homosexuals as nothing better or worse than himself, as people with an equal right to pursue their life dreams.

As stroller after wide stroller pumped into my chair on the sidewalk, even Mark was struck by the number of little children on the street and the elaborate means of conveying them. It seems to be often the father who pushes the stroller or who wears the baby backpack. We heard baby babble and children’s voices on all sides of us.

“It’s hard to believe there are so many little babies here,” Mark said.

I didn’t think there were necessarily more children per capita. However, it seems that the people are much more willing to take their small children into public and that the public welcomes them. In the National Museum, an interactive section had all kinds of interesting hands-on activities for kids and adults, who might otherwise be bored in a historical museum. Restaurants have play corners. There are changing areas almost everywhere. Airports and museums have strollers on hand for visitors to use, for free.

Looking at all these babies of course makes us think of our little River. I spoke to him by phone last night and he said “mama,” a single word that filled my heart with joy. But he didn’t say it with longing, but rather curious interest. As I continued to speak to my father, I could hear him happily babbling in the background. He seems to be doing just fine without us.

Seeing all the little babies is also awakening a nascent desire for another. Not now, not yet. But someday I’d like to have that experience again. Our travel companion on this trip said that in Sweden, more educated families tend to have less children, because they want to do other things in life. I don’t know if it’s possible, but I want to have it all. I want to have children and a loving family and have a life full of rich experiences. We’ll see whether or not it can be done.

Labels:

babies,

gay pride,

Iceland,

Reykjavik,

travel without child

Monday, August 3, 2009

Icelandic children through the ages

Here are some toys played with by Icelandic children in earlier times. The first is a collection of bones. The second is a play village. The bones scattered about the village were used to represent animals in the community.

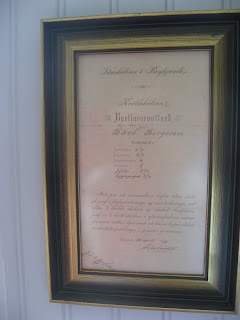

Here is the report card of a little boy from 1910.

He studied in a schoolhouse like this one.

Children often slept together with the entire family on one floor of the house. Or at a minimum, in a room with several beds, like this one.

Our tour guide told us how his grandfather had 14 children, all from the same wife. They all slept together in the loft of the house. When the guide asked his grandfather how he got the privacy needed to sire more children, he said he scattered raisins across the floor of the house on the lower level. If he needed extra time, he had the children wear mittens.

Saturday, August 1, 2009

Icelandic parenting

I’d read that Iceland is very welcoming of children and in my few days here, I can see that is true. At the local swimming pool, there are Bumbo seats and high chairs in the locker room, so women can shower comfortably. They have floaties, waterslides and toys for kids in the pool. Stores and restaurants have corners where children can play while their parents tend to their business. Babies are strolled down the streets in elaborate and expensive strollers. They are left in the strollers outside the shops while their parents shop.

Icelandic parents give their children a lot of independence. The attitude is that with a little bit of help, children will eventually grow up. That seems to be a lot like my own attitude. They are also taught to work hard, to value independence and quality and to see other people as equal and as entire human characters, regardless of social class. Those also resemble the values I was raised with and would like to pass on.

Boys and girls are raised the same and children are given a lot of independence. The family is the focal point of society and close relations are maintained. The downside of the high levels of independence, combined with both parents working longer hours than standard in Europe (but I imagine, less than in the U.S.) is that Iceland has had the highest rate of childhood injury needing medical attention within Europe.

We are living in the home of an Icelandic family while they are on vacation. The 17-year-old has the entire upper floor to himself, an oasis of privacy, while his parents share a bedroom with their five-year-old daughter. There are no closets in this 104 year old house and space is tight. All of the child’s toys and clothing fit into a small corner until the stairs. Yet she doesn’t lack for anything. She has only three pair of shoes, but all are stylish. Her dresses look like they could be worn by models. Her bed has a princess-like canopy. The parents also have a minimal number of items, but what they have is beautiful and well-maintained.

As we prepare to buy our first home, an older home that also doesn’t have much storage, I’m getting a good reminder in how much space is really needed (nothing near the average used in the U.S.), how to minimize and declutter, and how happiness is not correlated with quantity of belongings. Instead, the Icelanders believe, and I do too, a child benefits from close family ties, the opportunity to be independent and explore, quality and equality.

Icelandic parents give their children a lot of independence. The attitude is that with a little bit of help, children will eventually grow up. That seems to be a lot like my own attitude. They are also taught to work hard, to value independence and quality and to see other people as equal and as entire human characters, regardless of social class. Those also resemble the values I was raised with and would like to pass on.

Boys and girls are raised the same and children are given a lot of independence. The family is the focal point of society and close relations are maintained. The downside of the high levels of independence, combined with both parents working longer hours than standard in Europe (but I imagine, less than in the U.S.) is that Iceland has had the highest rate of childhood injury needing medical attention within Europe.

We are living in the home of an Icelandic family while they are on vacation. The 17-year-old has the entire upper floor to himself, an oasis of privacy, while his parents share a bedroom with their five-year-old daughter. There are no closets in this 104 year old house and space is tight. All of the child’s toys and clothing fit into a small corner until the stairs. Yet she doesn’t lack for anything. She has only three pair of shoes, but all are stylish. Her dresses look like they could be worn by models. Her bed has a princess-like canopy. The parents also have a minimal number of items, but what they have is beautiful and well-maintained.

As we prepare to buy our first home, an older home that also doesn’t have much storage, I’m getting a good reminder in how much space is really needed (nothing near the average used in the U.S.), how to minimize and declutter, and how happiness is not correlated with quantity of belongings. Instead, the Icelanders believe, and I do too, a child benefits from close family ties, the opportunity to be independent and explore, quality and equality.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)